We recently learned about a sacred gum tree that was saved through crowdfunding – a wonderful reminder of the importance of preserving natural landmarks.

A few months ago, we stumbled upon an article about a sacred gum tree, which is up to 400 years old. Called Me-Mandook Galk, or “beautiful grandmother tree”, the tree is sacred to the Dja Dja Wurrung people, who raised $150,000 to buy the land on which it sits. Now, future generations can gather around Me-Mandook Galk to connect with Country.

It’s a story that caught our eye because we love the idea that natural landmarks are rich with meaning. Can inanimate objects – trees, air, rocks – be imbued with spiritual soul?

We often design interpretive graphics for heritage sites, where natural landmarks, like an old tree, can be a strong and interesting placemaking feature. At Newmarket Randwick, there is a majestic Moreton Bay fig that once sat adjacent to Newmarket’s famous thoroughbred auction site. Today, it’s a gathering place for visitors and residents of Newmarket Randwick. At its foot, we designed historic photographs to show how the sales ring has evolved since 1914 – a simple example of how easy it can be to incorporate natural elements into future precincts.

Organic architecture and building on Country

In Sydney, spaces are constantly being developed, but sometimes the pace of development feels so rushed. Should we take more time to weave natural landmarks, history and character into built environments, and learn from those who have lived on this land for the past 65,000 years?

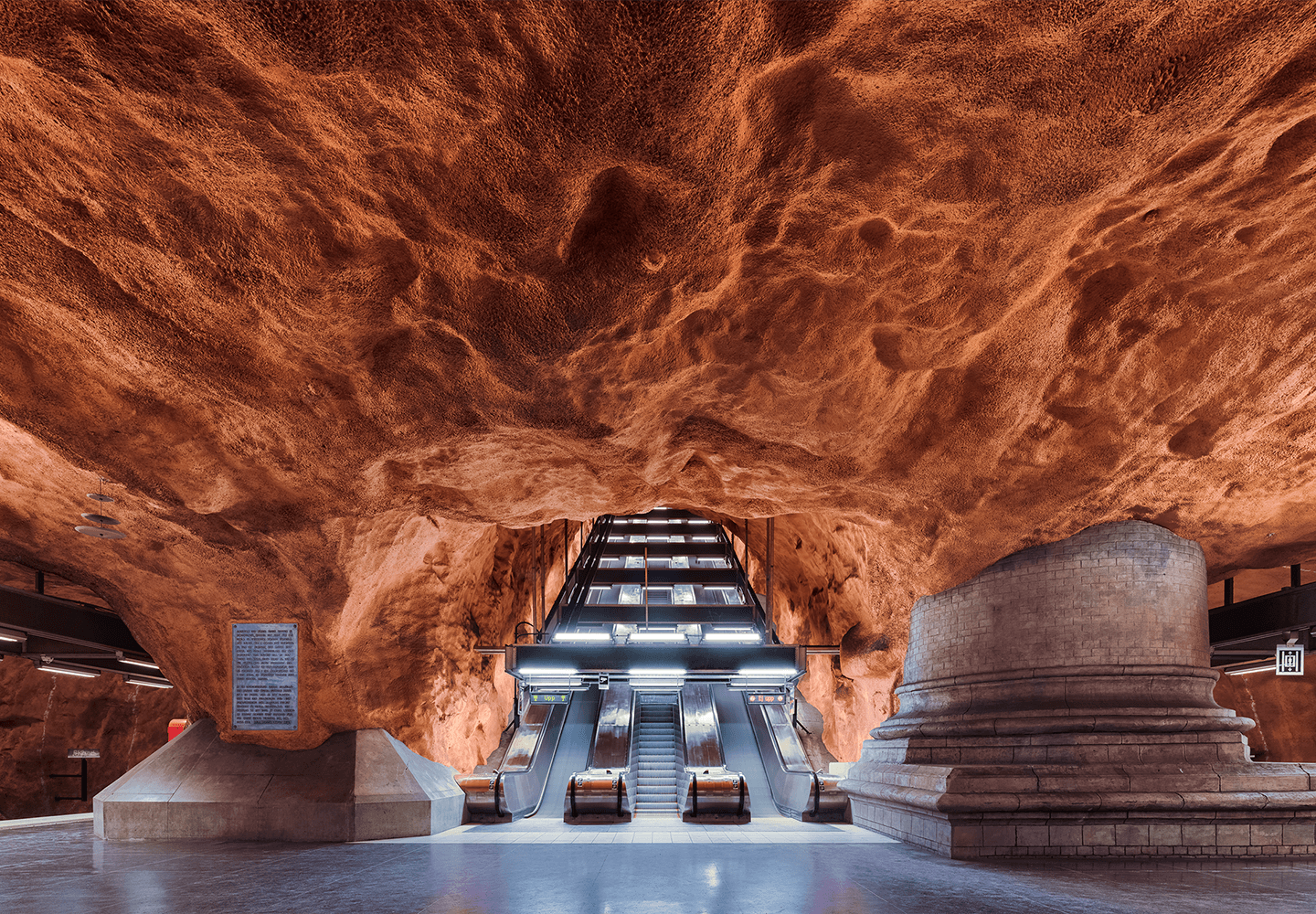

Organic architecture is another branch of design that promotes harmony between the built environment and the natural world. The most famous example is Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, a house built directly over a waterfall. Rådhuset metro station in Stockholm (pictured above) is also remarkable. Its cavernous station walls are made of exposed red rock, similar to the Cutaway in Barangaroo – both striking examples of how natural materials can be incorporated into new structures.

There is also so much we can learn from the oldest living culture in the world: Indigenous Australia. Alison Page, architect and Wadi Wadi woman, is the author of a book called ‘Design: Building On Country’ and believes all buildings, no matter their use, should be an extension of Country.

“Think of a building as an artefact. In our belief system, it’s a living entity, a member of our family, a functional tool for living or working in. It becomes this vitalised energised artefact that we engage with every day, which is a hell of a lot more meaningful than how we view architecture now,” she says.

As designers, we have a responsibility to design spaces that are more respectful of nature and the stories that came before them. As Page says: “[Indigenous Australian] systems, technologies and social structures were designed with care for the land, sea and sky and the people in them as a guiding principle. Isn’t this something we as Australians can all embrace as our identity? …. This knowledge helped Aboriginal people survive on this continent for 65,000 years. So if we want to survive for another 65,000 years, we should be treasuring it and appreciating it.”

Read the original article about the sacred Me-Mandook Galk, “beautiful grandmother tree”, here. Below from left: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater house; Newmarket Randwick’s majestic Moreton Bay fig with interpretive graphics by BrandCulture; the Cutaway in Barangaroo.